The Importance of Game Selection to Maximize ROI in MLB DFS

Game selection is as imperative to maximizing success at DFS as bankroll management and strategic lineup construction. One can practice proper bankroll management while making great lineups every slate and still (at best) be greatly capping their ROI by putting their lineups in the wrong contests. This isn’t just the cash allocation versus tournament allocation problem many DFS players experience. Underneath the cash and tournament umbrellas contain a wide variety of contests. Each contest type with various degrees of variance baked into the structures via pool sizes, entry limits, and payout tiers.

The more variance is in a contest, the more volatility will be in our results, so we will have to craft our lineups and allocate our bankroll accordingly. In this article, we’ll discuss how the amount of entrants, rake, and payout structures affect that variance and therefore our ROI.

CASH GAMES

In cash games, the payouts are as flat as they get—specifically in head-to-heads (h2hs), three-to-five-man leagues (3m-5ms), 50/50s, double-ups and triple-ups (DUs/TUs), along with bigger multipliers to some degree.

In a head-to-head where we face one opponent with one entry in a winner-take-all, the outcome is binary and dependent on one simple task: be better than one lineup. To be better than one lineup, we simply want to put the best-projected lineup forward, using good projections. What is referred to as the “optimal lineup” in DFS circles. In this case, we’re completely indifferent to ownership. The rake is a pretty standard 10% at the lower- and mid-stakes, so we’re only shooting for a better than 55.5% winrate in these contests. The h2h has the fewest variables of any DFS contest, making them the most simple to navigate.

The simplicity of the h2h is what makes them the most appealing to build and maintain a healthy bankroll. For many, there is more strategy in learning who to target than actually building a lineup. The lineup is most often just a matter of clicking “optimize” in a lineup builder after setting some preferences (or not setting any at all).

The 50/50s and DUs are similar in terms of lineup construction. We set an optimal lineup and register. Sounds simpler than targeting opponents in h2hs. But that simplicity comes with a price. It is typical to win nearly all or none of our DUs. Let’s say you finish in the 70th percentile or better in your 50/50s and DUs, you cash for nearly double your money. But when you finish in the 45th, you win nothing. In the first scenario, it’s pretty standard to win 80% or more of your h2hs with the same lineup. In the second, we can still get some money because we’ve won at 40% of our h2hs.

Outside of the margin where my lineups are so great or so terrible that I sweep or get swept in my h2hs, my bad nights in 50/50s still yield winrates of over 25% in h2hs.

Personally, 50/50s and DUs are my games of last resort because of the binary outcomes against so many opponents. They’re games to enter when the h2h options are exhausted.

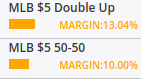

This brings us to why I actually never play DUs outside of NFL Sundays: the rake. The amount the site takes from each prize pool. The rake on multipliers—DUs, TUs, and the like—is 20-to-33% higher than on 50/50s and 3ms:

I don’t understand why I would want to play a game with a simple optimal lineup that requires such a higher winrate. But there are routes toward this personal choice. Namely, one has a $2.500 bankroll and is playing 80% in cash games and 20% in tournaments, totaling 10% of their bankroll—the common 80/20/10 suggestion.

Let’s say this person playing 80/20/10 wants to minimize the skill level of their opponents by sticking to $1 and $2 games where the highest of high stakes players are nearly eliminated from the entrant pool by a site’s regulations. Well, this person is limited to only 25 h2hs at each dollar level. 25 h2hs at $1 is $25 and 25 at $2 is $50, totaling $75, leaving $125 of the $200 allocated toward this slate to enter games. Play all the 50/50s you want under $5, it’s hard to avoid DUs. There is a way, though: small leagues.

3ms and 5ms are—at the lower stakes—a fantastic way to maximize ROI without deviating from the optimal lineup. They’re raked at 10%—the same as h2hs and 50/50s—with returns of $2.70 per dollar on 3ms and $4.50 per dollar on 5ms. 3ms require winrates of better than 37% and 5ms only better than 22.2% against the same level of opponents as the h2hs, 50/50s, and DUs.

At the higher stakes, some leverage tweaks are required to have a winrate that sustainably beats the rake, but contrarian play isn’t necessary to be profitable in these small leagues under $100 or so.

Anyway, back to our $2,500 roller practicing strong bankroll management and attempting optimal game selection. What should they do with the extra $125? $25 in 25 $1 3ms, $50 in 25 $2 5ms, and $50 in $1/$2 50/50s; or just bomb the 50/50s and tournament-level-raked DUs?

LEAGUES

If you have no interest in 10m or 20m leagues, there is still value in this section for you. Especially if you a novice at Guaranteed Prize Pool tournaments (GPPs) or stuck in MinCash Hell. If you’re a strong GPP player, I would recommend the leagues as supplemental bankroll builders to beat off the stings of the GPP swings, as you’re leaving money on the table.

These leagues get a little bit into the tournament mindset of incorporating leverage over the field. Because these fields are smaller, though, the leverage necessary is minimal, relative to fields of 50k, 5k, or even 500 people.

There is a trope that a GPP player usually finishes close to first or last and I’m not entirely sure that’s true, but it’s definitely true in these leagues for one main reason: the field largely makes the mistake of entering their optimal lineup into these contests.

We can exploit this mistake very profitably by incorporating correlation and ownership into our decision-making. In MLB and NHL, this is where we begin to stack; in NFL and NBA, this is where we begin to sacrifice some projected points for projected ownership. This is where we begin strategizing against our opponents’ decisions.

At smaller payout structures, but with far less variance and lower necessary winrates than GPPs.

A cash-style optimal lineup won’t suffice in these 10m/20ms, but chalkier GPP with strong projections will perform very well for us. That’s why these are great spots to begin getting out of the cash mindset and great ways to maximize the GPP lineups that consistently minimizing. For the chronic mincasher, money can start to be made; for the GPP shark, these are great alternatives to the cash games they frequently loathe. My favorite of these leagues, though, are the 100ms.

The 100ms can turn a GPP novice into a shark—especially on FanDuel, where the top-heavier payout structure is more suited to beat the rake. FD’s 100ms pay 12 spots, including 25x to first, 15x to second, and 10x to third, whereas DK spreads out the 90x prize pool among 20 spots, only dishing out 13.5x to first, 10.8x to second, and 8.1x to third.

The biggest shift from cash games to tournaments is the incorporation of correlation and ownership to create leverage, but the bankroll management pivot is a difficult one, as well. As recent as 2019, I was playing 90% off my daily allocation in cash games with complete attention to optimization and opponent selection and 10% in GPPs with no attention to detail for about 5-to-8% of my bankroll. Losing 10% of my daily wager was about as fun as peeing my pants during a makeout session.

The best advice I received in my DFS career was the pivot to 75:25 cash:tournament, but to play 80% of that 25% in 100ms and have a hard 5% daily rule as a maximum. I suddenly became a profitable tournament player by simply adjusting my game selection and bankroll management. My play improved, sure, but that was largely from the safety I had secured in the bankroll management and sustainability gained by the increased profits from game selection. A sustainable bankroll management program and game selection tailored to our goals give us the leash to try things in order to learn and grow. To be fearless and thorough from the very start.

Doing the same thing over and over again, expecting a different result is the definition of having one’s head up said person’s ass.

SINGLE ENTRY and THREE-MAX GPPs

The old school fields would commonly put their cash lineups into the single entry GPPs. This is far less of a norm, becoming more of an exception, but it still exists to a degree of significance. Less so for the GPPs with a maximum entry of three lineups, but the practice still exists. Enough to pay the rake.

The single entry and three-max (SE3s) GPPs are where the practice of playing the 100ms is most valuable. The winrates are lower in SE3s than 100ms because the fields range from 200 around the $100 level to 1k at the $50 level to 10k at the $1 level, so our play has to vary accordingly.

As we’ve discussed: as the variance of a contest increases with field size, so does the need for us to differentiate in order to: (a) avoid duplication with individuals: and (b) separate ourselves from the field as a whole. My lineup in a 200-person SE3 field is going to have higher projected ownership (pOWN) than that of a 1,000-person field, regardless of the buy-in.

As long as our pOWN is separated from that of the optimal lineup, in terms of projected points (pPTS), we can survive in small-field SE3s as we did in 100ms, but this where the double-stacking in MLB DFS is closer to imperative than the 5-1-1-1 on DK or the 4-1-1-1 on FD; avoiding the QB-RB negative correlation plays more for NFL; and fading expensive NBA chalk can double in leverage, relative to the larger fields. This is where we begin to evaluate our deviations from the optimal lineup in terms of expected value (EV).

EXPECTED VALUE

Let’s keep this simple.

EV is the probable reward (Pr) relative to the probable outcome (Po).

In DFS, the Pr is tricky because it isn’t a full pot to be received in a poker hand. There is a variation of payouts, but the amount of possible total points required to finished first, second, or tenth, or even cash, is infinite relative to a poker tournament with a finite quantity of chips in play. Because of this infinity element, we look at many variables: the percentage of the prize pool to the top spot; the percentage of the prize pool to the top-three; the percentage of the prize pool to the top-five; and the like, all the way down to the minimum prize to cash and the percentage of the entry pool who can cash. We do this to gauge how flat the payout structure is. The lower the percentage of the prize pool goes to the top spots, the flatter the structure.

Po is as impossible to quantify with pinpoint accuracy in DFS as Pr is, but it is along the lines of: maximum pPTS for the minimum pOWN. The mistake of maximizing pPTS, indifferent to pOWN, is that everyone is trying to maximize pPTS, paving the road to MinCash Hell—where the low frequency of cashes, baked into tournaments, does not cover the losses of not cashing. The mistake of minimizing pOWN is that sacrificing too many pPTS leads to not enough cashing, especially in those flatter structures where playing for the top-0.1% or bottom 1% carries a lower Pr.

Practically speaking, without a perfect algorithm to discover the sweet spot of pOWN relative to pPTS for every Pr, EV isn’t calculated so much as estimated by us to name some rules:

- Science: the larger the field and the less flat the payout structure, the more leverage we need to have to be profitable.

- Art: we create leverage largely by minimizing projected ownership in our lineups at the minimum sacrifice of projected points.

LARGE FIELD and MASS MULTI-ENTRY GPPs

We’re gonna lump large field SE3s (2k and more entrants) and 20-to-150-maximum-entry GPPs (MMEs) together. They play differently, but they share some rules.

Large field SE3s and MMEs require meta-elements of leverage to different degrees. Much higher than the smaller SE3s. Where we are uncomfortable with sacrificing pPTS to these levels to garner EV, we should allocate single digits of daily allocation toward these contests, if not ignoring them altogether. It isn’t uncommon to go a year without winning one of these GPPs and the lack of flat payout structures requires so many top-five—if not top-three—finishes to stay afloat, let alone make a profit. If these goals are not accomplished, chinks in the bankroll management armor will quickly be exposed and you will go broke.

The common mistake made among losing GPP players in the pivot toward cheap MME games and entering as many entries as their bankroll can withstand by whatever measure they choose. If you’ve read to this point and have seen where your game can flourish in the other games, go heavier on those games and wager an insignificant amount on your MME play.

Full disclosure: I don’t play MME. Those fields are so massive that I’m uncomfortable putting that degree of thought into contests. I don’t avoid them altogether. I do put one-to-five entries into contests in the $30-$75 range with large prize pools, but for only under 5% of my total allocation on the slate. Because, you never know, right?

But a lot of these contests where you barely 12x or even 20x your entry fee for finishing in the top-ten require extreme bankroll care in fields where our opponents are putting 20-to-150 entries in. If you wanna put in $100 worth of entries into a $5 contest paying $100k to first place, have at it. But a $100 in a high variance contest that requires higher variance lineups to garner any EV is a stressor on a $5k bankroll, let alone a $1k bankroll.

RG EXTENSION

The RotoGrinders browser extension does the work for you on calculating rake and displaying it for us right in the lobby:

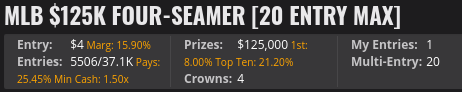

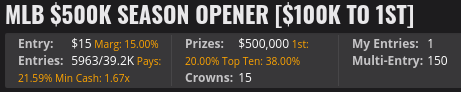

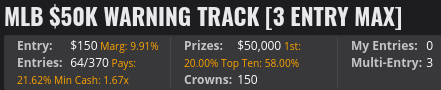

We can see that the rake for a GPP with an entry fee over $100 jumps 20-to-33% for the GPPs of around $50-to-$99 from 9-10% to around 12%. And a whopping 50-to-60% when you get into the lower stakes. The payout structures of these GPPs can be seen by clicking on a tournament info to reveal huge differences in every contest.

Compare the flat payouts for the $4 large GPP, not paying much to first and only 20% to the top-ten, but a quarter of the field cashes:

To the immensely top-heavy structure of the $15 MME contest:

To the low-rake, but still top-heavy $150 3-max:

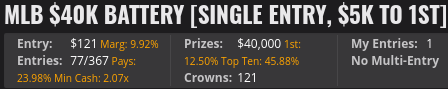

To the also low-raked, but flatter, higher-mincash structure of the $121 SE that still rewards a good chunk to finishing top-ten:

There is a multitude of options when it comes to the structure of an event, crossing over prices of entry. These are just a few GPPs lined up for one slate in one sport. Use the RG DK extension as well as the FD extension where the work is done for us in order to make educated decisions regarding game selection.

BANKROLL MANAGEMENT

There is a way to roll with those 20 $5 entries in the effort to bink a big one, though: the other 80% of your daily entry fees on the lowest of low variance cash games. See a pattern here?

- The higher variance in a contest, the higher the variance in the lineup; just as

- The higher variance in a contest, the higher the quantity of low variance contests need to be played within the slate

There is a way to secure a steady roll as a mid-stakes SE3 player for 20 or even 25% or even 33% of the daily allocation.

- The higher variance in the contests, the lower the percentage of the total bankroll ought to be allocated toward the contest.

You can play 100% of your daily allocation in GPPs, but it’s suggested that this is no more than 2-to-3% of your overall bankroll and that there is a diversity of game selection. Mix in the leagues and SE3s with a lineup different from your MMEs.

There are no hard rules regarding game selection and bankroll management, only suggestions from people who’ve avoided going broke for years and years, withstanding long cold streaks and not over-extending after big scores. Play whatever games you want. There are many paths to glory. Just remember the axiom which does exist:

- The higher the variance, the more leverage needed in the lineups, meaning the tighter bankroll restraints are necessary.