MLB Player Projections: Foundational Knowledge

If you’re not using projections as part of your DFS process, you’re either a losing DFS player or you’re leaving money on the table. That may sound blunt, but it’s true. Please. Spend five minutes. Read this article. Try to be open-minded. And I promise you will become a better DFS player by the end of it. Even if you already use projections, there are key things your projections need to be doing, and if they aren’t, you may want to reevaluate.

Editors Note: You can find THE BAT projection (referenced in this article) here

Why Are Projections Important?

1. All the top players use projections

You won’t find a single truly successful DFS player that doesn’t use projections as part of their process. Some may not admit that they’re using them or won’t reveal what their projection process looks like in order to maintain their edge. Some players who don’t use projections try to come off as being successful, even if they aren’t, in order to sell you something. But rest assured: all the truly best DFS players use some form of projection. Which begs the question: why aren’t you using them? Especially because…

2. Using projections saves you time

So many DFS players waste countless hours digging into splits and umpire data and weather and Statcast metrics and tons of other data points, then manually analyze the data to try to figure out who the best plays are. THIS IS A WASTE OF TIME! Why? Because…

3. Projections accounts for all the things you’re trying to account for, but they do it better!

There may be a few exceptions, especially with lesser systems, but a good projection system will account for all of the important things. All of the things you’re researching manually should already be in a good projection… which is why it’s important for a projection system to be transparent about what goes into it so that users can spend their time on whatever doesn’t go into it, or on the non-player evaluation aspects of DFS (ex. lineup-building); this is always a goal of mine with THE BAT. For example, if you don’t know what goes into the projections you use, you may spend a bunch of time researching weather for every slate. But if the projections already account for weather, guess what? Now you’ve accounted for weather twice. You’ll overestimate its impact, you’ll be too heavy on players from those games, and in the long-run all that extra work will actually LOSE you money. And finally…

4. Using projections is more accurate than not using them

Everybody uses projections—even people who don’t use projections. Yes, you read that correctly. Let’s say you refuse to use projections and just build lineups manually. You have $5,000 to spend on an outfielder and go with Charlie Blackmon over Aaron Judge. Well, even though you didn’t use projections to make that decision, like it or not you still implicitly “projected” Blackmon to score more points than Judge. By the very nature of making that decision, you made a “projection.” Blackmon projected higher than Judge. If he didn’t, you wouldn’t have picked him. But instead of using a true projection, instead of letting math form that projection, you let your brain form it, using all sorts of guesswork and estimates that will always be less accurate than the full math—especially since that math is working with the same data you are, but it’s crunching that data in a much more precise way..

What Exactly Is a Projection?

While some people think of a projection as a definitive “this is what the player will do” number, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Projections deal with probability, and anybody trying to sell you on certainty or guaranteed results is a liar. A projection represents the most likely outcome… but it’s certainly not the only possible outcome. One of the best ways to think about it: imagine a million parallel universes where the same exact matchup was played out a million times. A projection represents the average outcome from all of those universes. Sometimes Mike Trout will hit a home run in the game, many times he won’t, very rarely maybe he’ll hit two or three or four. But on average, across those million universes, maybe he hits 0.30 home runs in this game, and that becomes the projection. It’s not set in stone, but it’s our best guess at what the player will do given all of the information at our disposal.

Some people will say “How can you project 0.30 home runs?! That’s so stupid, either he’ll hit a home run or he won’t!” But, of course, when you think about it in terms of probability, it makes complete sense, and projecting either 1 HR or 0 HR is what would actually be stupid; presuming we have that level of certainty is stupid.

Traditional projections represent the mean (or median—this is a minor distinction that’s not important enough to get into) outcome, but because projections actually represent the average of all possible outcomes, you may also see “floor” or “ceiling” or various “percentiles” or “range of outcomes” projections. For cash games, mean projections are best. But in GPPs, you may want to use a higher percentile. It’s a less likely outcome, but that upside is more valuable in a top-heavy contest. Here’s an example of THE BAT’s range of outcome projections:

Why Use Projected Stats When We Have “Real” Stats?

Some people wonder why they should use a projection when they have “real” stats to look at. Why should they care about some “made up number” when they know what the player actually did? (I’ve had real people say this to me. Edge will never completely die in DFS, I promise.) The short answer is because it doesn’t matter what a player did, it matters what they will do in the future. And it is a 100%, proven fact that projections do a better job of guessing what will happen in the future than past stats do. This may seem obvious to some (it’s what projections are designed to do, after all!), but it’s important to note nonetheless. If you don’t believe this, you’re just donating money.

Think about it like this: let’s say we have a player, and all we know about him is that he has played one game with one at-bat and one hit. If we want to know what he’ll do in his next at-bat, would you ever look at his past stats and say, “Well, his batting average is a perfect 1.000, so I know with absolute certainty he’ll get a hit in his next at-bat!” I hope you’d never say that, because it’s insanity. One at-bat is a very small sample size and a poor predictor of future performance. Maybe the player is good, or maybe he just hit a weak blooper that fell in over the second baseman’s head.

In reality, we deal with larger samples than one at-bat, and somewhere along the way the human brain tries to tell us, “Okay, this is big enough, now we can trust it!” For some it may be after two months, or half a season, or two seasons, but eventually people start to think they’ve seen enough and that what they’ve seen most recently must be reality. If your brain tries to tell you any of this, IGNORE IT! Why should we rely on what we think is good enough when we have the mathematical tools to prove when a sample is big enough?

First Principle of Projections: Sample Size

That brings us to the first basic principle of a projection: dealing with sample size. Instead of guessing when a sample size is big enough, we can run tests. They may tell us that, say, strikeout rate stabilizes very quickly and that our sample can be relatively small before we start to trust it, but that BABIP stabilizes very slowly and we can’t trust it very quickly at all. More than that, though, it puts an exact number on this “trust” that will be more accurate than any subjective judgment the human brain comes up with. It then uses that number to better project players using a concept called regression to the mean (which is a little too involved to get into here, but know that it’s all about dealing with sample sizes).

Second Principle of Projections: Multiple Weighted Seasons

A lot of DFS players just look at the current season, or the last couple seasons, do some mental averaging of them, and using that to form their impressions of players. A good projection system will run tests for this just like it did the first principle. It will determine, for every stat and player type, how many years of data is optimal to use and in what proportion. (The most recent data will almost always be most important, but how much more? Twice as important as the year before? Three times? Ten?) A good projection will always try to maximize accuracy, and it will use past data to determine the best way to do that. If using data in XYZ proportion maximized accuracy for trying to project the 2000-2019 seasons, it stands to reason it will be pretty damn accurate when projecting the 2020 season.

Third Principle of Projections: Player Aging

Players get older. When they’re young, getting older means they get better. When they’re already old, getting even older means they get worse. (Generally speaking). But again, how much better or worse? We can either guess, or we can run tests, figure out the exact amount, and put that into our projection.

Fourth Principle of Projections: Context

The first three principles are the absolute bare minimum any halfway decent projection system must have. If you’re using projections that don’t do all three of those, find a new system, because it’s bad. And for DFS purposes, this fourth principle really needs to be involved also. For example, everyone knows that a player will hit better in the thin air of Coors Field than he will at any other ballpark. A good projection should know that.

As far as I know, THE BAT is the only projection system that looks at the context of every at-bat that every player has ever taken. It looks at the ballpark, the opposing pitcher/hitter, the defense, the catcher, the umpire, the weather, etc. for every single at-bat, and then adjusts the player’s stats accordingly. Did the batter play in mostly hitters’ parks on hot days against weak pitchers? Well, maybe his numbers are inflated because he faced easy conditions. We should account for that, but it would be impossible to do without a computer running all that data for you. Then, of course, once you adjust the past numbers and form your baseline projections from them, you want to adjust for all of the context he’ll be facing in today’s game to get your final projection.

What About Advanced Metrics and Statcast Data?

It’s common for DFS players to say, “Well, this is all fine for ‘stats’, but I focus on ‘skills’ from the new Statcast data, so I don’t have to worry about sample size or using multiple years of data.” This is one of the most common traps that players fall into these days and gives those of us smart enough to avoid it a big edge. Yes, Statcast stats are a bit more stable than traditional stats, but not by much. Here’s how they stack up:

Even though things like Launch Angle and Exit Velocity and Barrels are better than more basic stats like groundball rate or home run rate, they only stabilize like a week sooner. It’s really not that much different, and so everything we talked about applies to them too.

What About Splits?

A good projection will account for splits to the extent they matter which, in most cases, is very little. A bad projection will use splits without understanding how much noise is in them.

Many studies have shown that splits have very little predictive accuracy, so don’t get bogged down in trying to slice and dice data every which way. In trying to make the data more relevant, you really just reduce your sample size and add extra noise.

Some DFS players will look at home/road splits, which are entirely meaningless. The three things that impact home/road splits are park factors, generic home field advantage, and variance. A good projection already accounts for the first two, so why would we want to introduce more variance? You just wind up splitting your sample size in half, throwing away good data, and losing accuracy. Use all of the player’s data, adjust for the parks, adjust for the home field advantage, and you get much more meaningful information.

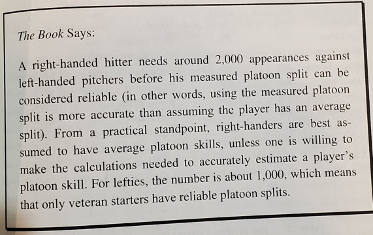

Fantasy players also love to focus on righty/lefty splits… to their own detriment, usually. The premier sabermetric book, “The Book: Playing the Percentages in Baseball”, says this about hitter platoon splits after running all the math:

As much as people want to believe that Wilmer Flores or James McCann or whoever is a “lefty masher”, the math just doesn’t support it. Unless you’re running the full math—like a good projection system will do, but which I’m not sure many besides THE BAT actually do—you’d be better off ignoring a player’s split entirely. Plenty of bad projection systems just use the splits at face value, which is why (once again), it’s very important to know what goes into whatever projections you’re using.

“But Projections Are Wrong So Often!”

This is a common criticism of projections, and it’s completely off base. No process is perfect. Projections. No projections. Doesn’t matter. We can never project the future with absolute certainty. We talked about the million simulations and the range of outcomes. Sometimes, an elite pitcher like Max Scherzer gives up 10 runs to the awful Miami Marlins offense. That may only happen in 1% of those million simulations, and if it happens today when you roster him, it sucks. But that doesn’t make the projection “bad” or “wrong”. It just means that today, that very unlikely outcome happened. After all, even if something only happens 1% of the time… it still happens 1% of the time!

But What About [Insert Non-Mathematical Player Quality of Your Choice]?

Projections try to account for as much as possible, but there are certain things that many projections don’t account for, and there are certain things that no projection is able to account for. Some things are just too subjective or are unable to be represented as numerical data. Nothing is perfect, but a projection gets you as close as you can get. Even if you just use them as a starting point and layer your own research on, still USE THEM! Folding a quality scouting take into your process, for example, would be one way to add additional value to a projection.

Just Be Sure Not To Double Count!

I can’t state this enough: before you use any projection, know what goes into it! How can you trust that your projections are good without knowing how they’re built?! With THE BAT, I lay out what goes into it, what doesn’t, and am always available to answer any questions users have. Whatever projections you use, make sure you receive the same level of transparency.

Use THE BAT!

I am entirely biased, but I truly believe that my projection system, THE BAT, is the best system available. It accounts for more factors than any other system I’ve seen. It uses the same methodology that MLB clubs use as part of their own processes (I know this because I’ve worked with many people who make decisions for clubs). It consistently ranks at or near the top of accuracy contests. It uses Statcast data now. And most importantly, users love it and usually make money. If you want to learn more, please check out more details here or feel free to send me a DM on Twitter (@DerekCarty).