NFL Best Ball Strategy: Roster Construction Part 2 - Elite QBs

![]()

I’ve said it several times already, but there are a myriad of “right” ways to build a Best Ball roster – we want to be flexible and apply the best approach for each specific draft. That said, there are some universal rules that I follow, especially when it comes to quarterback. We do not have a lot of room for creativity at quarterback. We can only start one each week, and unlike at tight end, we cannot use a quarterback in the flex. I provided my high-level guidelines to quarterback in Roster Construction Part 1 but I did not provide very detailed analytical support in that piece.

To review, here are the quarterback “rules” that I provided in the first roster construction article:

When to Draft 2

- 1 Very Early, 1 Late/Very Late

- 2 Early/Mid

When to Draft 3

- 2 Mid, 1 Late/Very Late

- 1 Mid, 2 Late/Very Late

- 2 Late, 1 Very Late

- 3 Late

Editor’s Note: Use promo code “GRINDERS” when you sign up for Draft and get a 100% deposit bonus up to $600 and THREE months of RotoGrinders Draft Premium content!

Today, I want to focus on what to do when you draft one of the top quarterbacks (e.g. Aaron Rodgers, Tom Brady, Drew Brees). Why, when we draft a “Very Early” quarterback, should we wait until late or very late to draft another?

Elite Quarterback Strategy

If you have tuned into any of the Thursday night Grinders Live Best Ball Drafts, there’s a good chance you’ve heard me groan when the first quarterback came off the board, and in a couple of cases where one of my colleagues drafted two early quarterbacks, I submitted a friendly “booooooo!” I have heard the arguments that a team with two elite quarterbacks is very likely to have one of the best scores at the position each week, and that there is the bonus of keeping a good QB off of opponents’ rosters. Both of those statements are true. So why does it get me so riled up? It bothers me because our job is not to score the most points at quarterback each week – our job is to maximize the score of our entire starting lineup over the course of the season. That is how we win.

Just as we did in the handcuffing analysis, let’s break the two-elite-quarterback strategy into benefit and cost. Again, I will start with the potential benefit.

Benefit Analysis – Value over Drew Brees (VoDB)

To measure the benefit of a second early quarterback pick, I needed a way to quantify and compare the value of various QB2 picks throughout the draft. Starting from a baseline of drafting one elite quarterback, I have compiled how many more points a best ball team would have scored given each potential QB2 over the past two years.

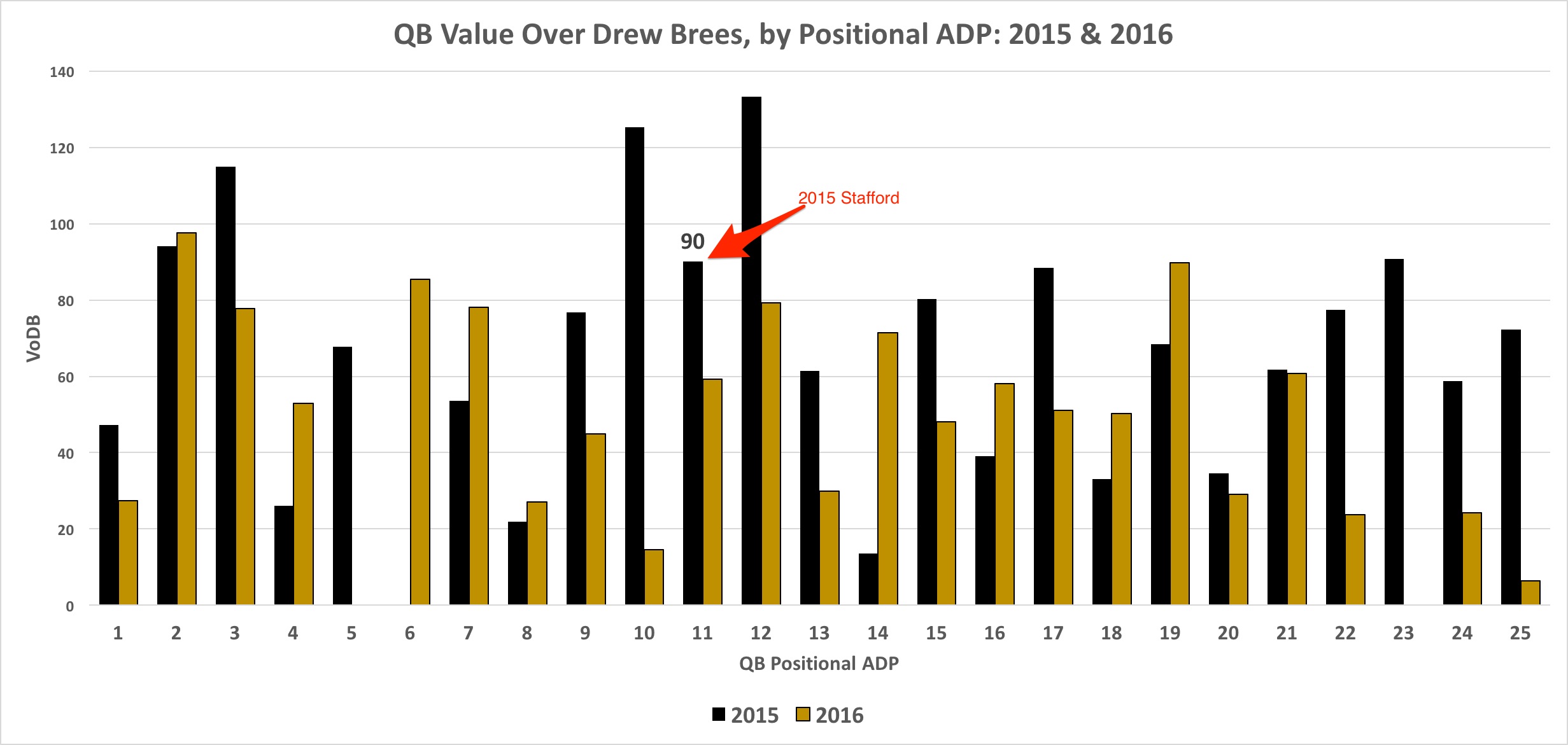

For my elite quarterback baseline, I have chosen Drew Brees, because in each of the past two years, Brees has both had a relatively high ADP (QB6 in 2015 and QB5 in 2016) and finished the season as one of the position’s top scorers (QB6 in 2015 and QB3 in 2016). The following chart shows how many points each quarterback, sorted by ADP, would have added to a Drew Brees Best Ball team’s total score, above what Brees produced on his own. For example, in 2015, Brees scored 302 fantasy points (weeks 1-16), and a roster which had both Drew Brees and that year’s ADP QB11, Matthew Stafford, would have scored 392 at quarterback. So, while Stafford scored 280 total points, his Value Over Drew Brees (VoDB) was 90 (392 minus 302).

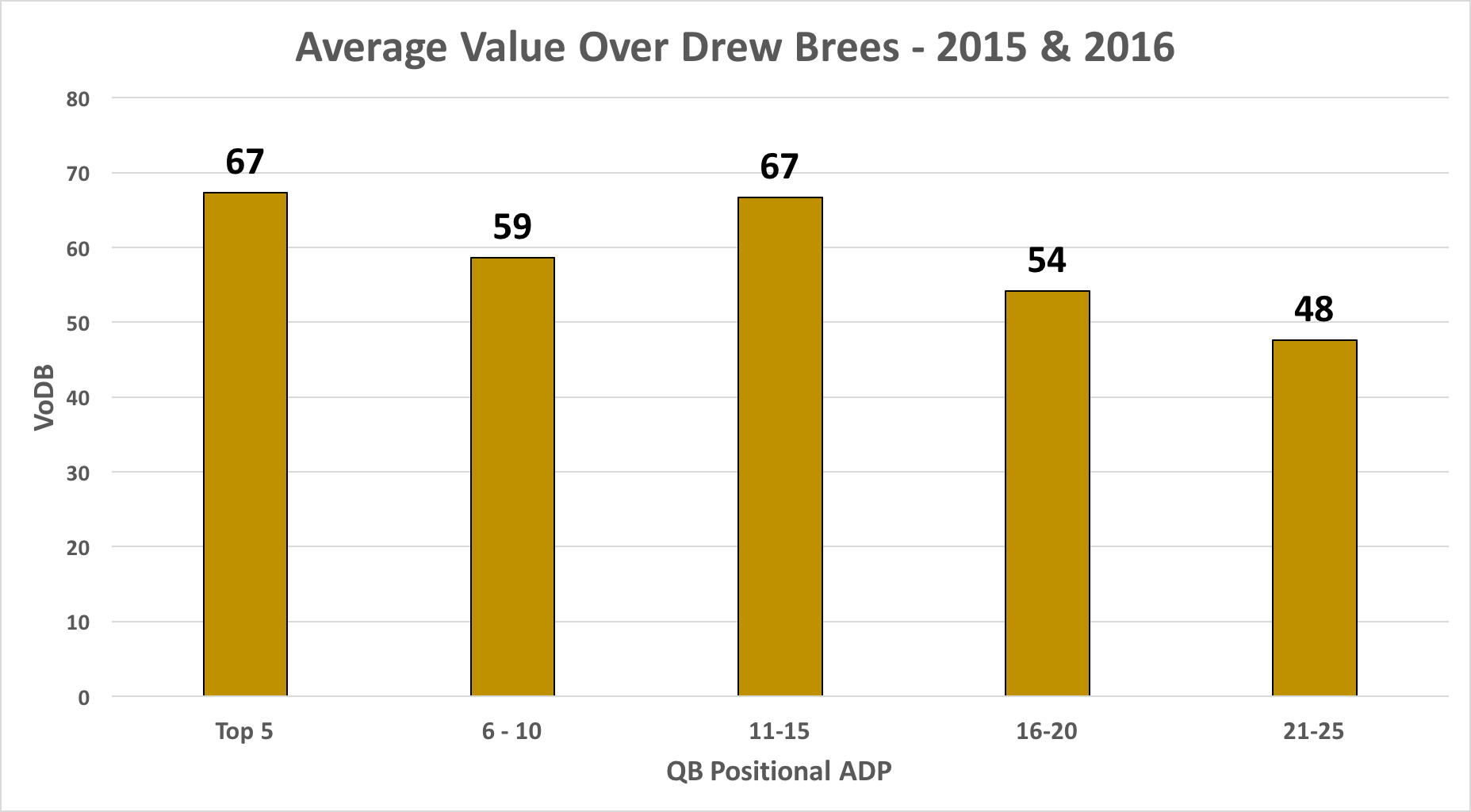

Now, here is the same chart, but using the averages for five-quarterback ranges.

Using this chart, we can get an idea of the expected benefit to our roster that a second QB from different parts of the draft adds when we already have what we expect to be an elite quarterback. We can see that the top-5 QBs tied for the best average, coming in 13 points higher than the “16-20” range, and 19 higher than “21-25.” We also know from the first chart that every range has at least one quarterback in the top quartile and one at least one in the bottom quartile (i.e. there are winners and losers in each).

Even before taking cost into consideration, it’s not clear that a second elite quarterback gives you the most points at the position relative to later picks. Let’s take a look at cost anyway.

Cost Analysis

Whenever we make a pick, the opportunity cost is the player that we could have had in its place. Currently, the top five quarterbacks have ADPs between the third and sixth rounds. Quarterbacks 16-20 (the group that has added an average of 13 fewer points to a Drew Brees lineup) have ADPs in rounds ten through twelve. To approximate the “cost” of quarterback picks in those ranges, let’s look at what players at other positions who have been drafted in those ranges have done.

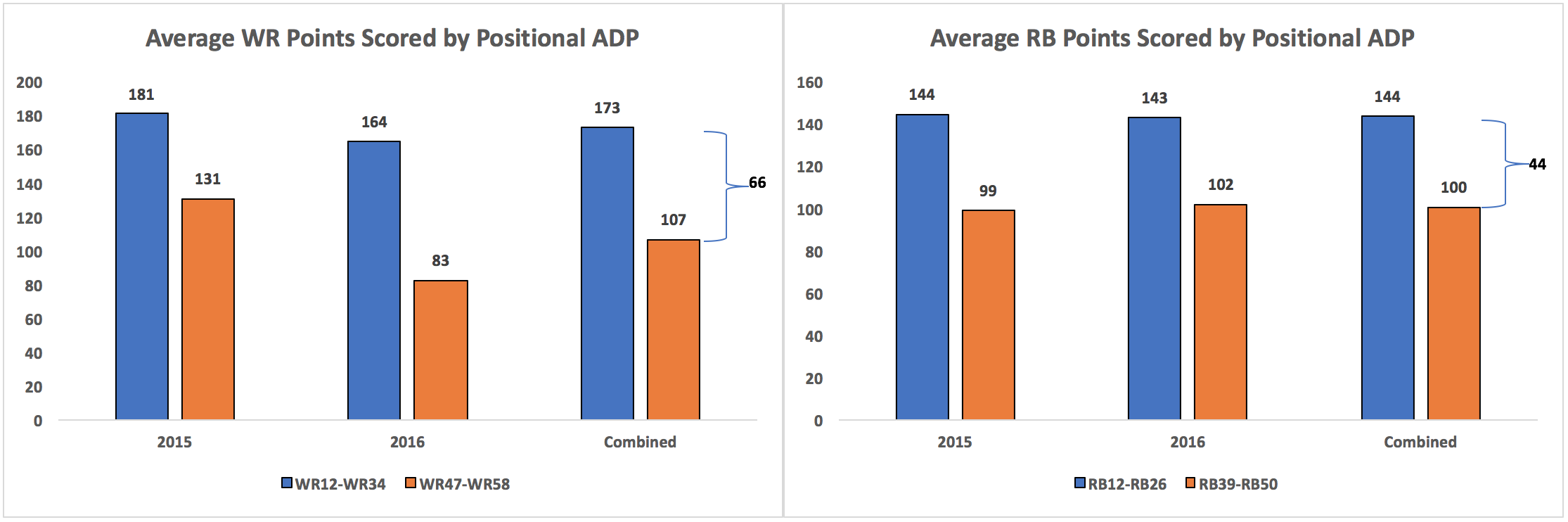

Currently, rounds 3-6 are home to WR12-WR34 and RB12-RB26. Rounds 10-12 are where we find WR47-WR58 and RB39-RB50. Here is what scoring looks like for those groups over the past two years.

The average wide receiver from the first group scored 66 more points than the average receiver from the WR47-WR58 group. Likewise, the earlier RBs scored an average of 44 more points than those in the late group.

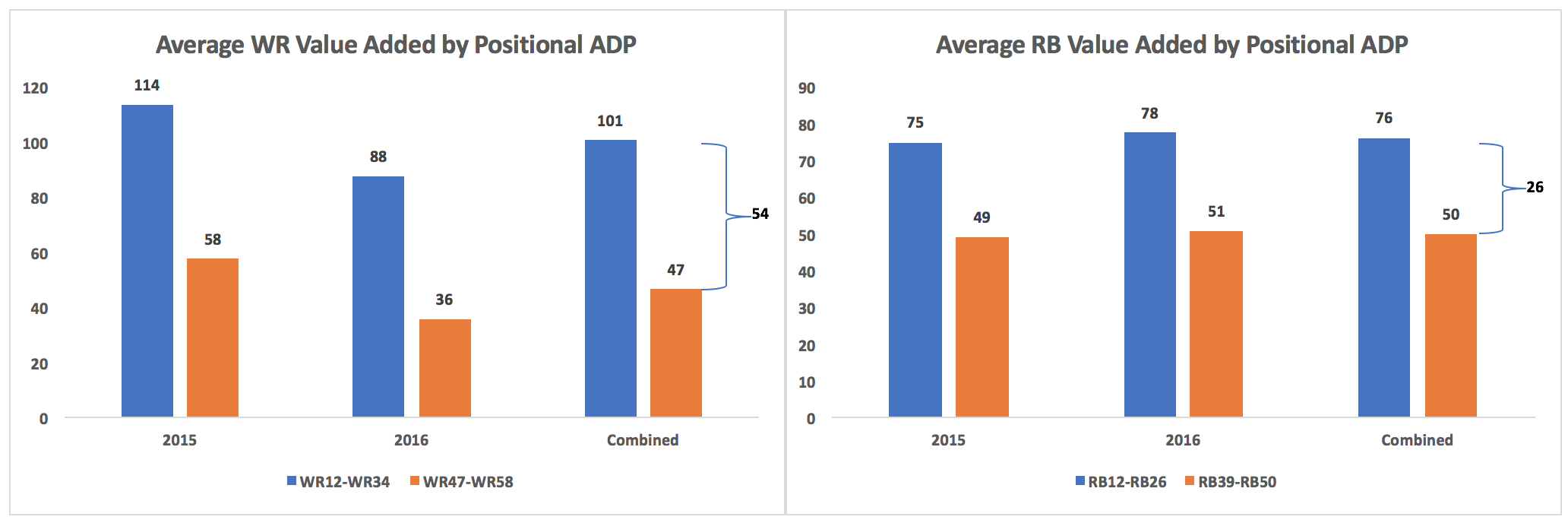

We don’t care about raw points, though. We care about points that actually hit our starting lineup. From my Best Ball database, I have been able to calculate the average “value added” of each player – meaning the number of points they contributed to starting lineups above what their rosters would have scored without them (e.g. if a WR filled the starting flex position with a score of 10 points, and the next best player on the bench scored 8 points, that WR added 2 points of value that week). Here are the same charts using average value added in place of total points.

Here we see that the average drop in value added is 54 points for wide receivers and 26 points for running backs. This represents what we are giving up when we choose to pick a second elite quarterback instead of waiting on QB2.

Conclusion

Based on this analysis, drafting a second early quarterback instead of waiting until the second half of the draft is a negative expected-value move – we gain an expected 13 points at QB while sacrificing 26-54 points at RB or WR. Of course, if you pick exactly the right early quarterback, and exactly the right WR or RB in the later rounds, you can end up with a stronger score at the end of the year, but that is not easy to do. What we want to do is tilt the odds in our favor each time we draft – hunt for the great picks in the areas that give us the best chance to win. By waiting until round 10 or later to secure your second quarterback, you still have the opportunity to hit a high scoring/contributing QB2, while making a meaningful improvement at another position. Whether you should take a top quarterback at all is a separate discussion and analysis, but if you find yourself liking the value and rostering one of the elite signal callers, keep this study in mind.

Good luck, drafters!