Risers and Fallers: Volume 4

![]()

I’m excited to be back for another week of Risers & Fallers! Each week, I’ll break down a handful of players using advanced metrics, insights from my scouting background, and my DFS projection system THE BAT (available in the RotoGrinders Marketplace), which consistently beat Vegas lines last year. I’ll examine guys whose stock is going up, guys whose stock is going down, guys who are perpetually underpriced or overpriced, guys who are worth paying a premium for, or guys who are just interesting and warrant some analysis on. If you guys have any suggestions for who you’d like to see in future articles, feel free to let me know.

This week: why Seth Lugo’s elite spin rate doesn’t matter, and why Hyun-Jin Ryu may be about to break out.

Rising… But Very Quietly

Hyun-Jin Ryu, SP, Los Angeles Dodgers

It wouldn’t be another week of Risers & Fallers without breaking down a Dodgers pitcher. Alex Wood (check it out here) and Rich Hill (check it out here) each got their turn, and now we’re looking at Ryu.

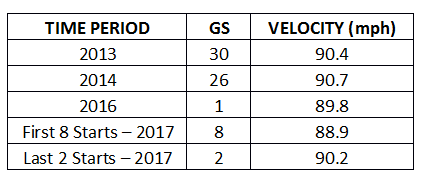

Ryu was once a heralded Korean import and impressed with a 3.00 and 3.38 ERA in his first two MLB seasons, respectively. Then he underwent shoulder surgery, missed all of 2015, and made just a single start in the majors in 2016 while experiencing setbacks. Now 30 years old, Ryu is something of an afterthought, having posted a 4.08 ERA and 4.15 xFIP through his first 10 starts of 2017. Ryu, however, might be something more than those very mediocre stats would indicate. Take a look at his fastball velocity levels over various time periods, and take particular note of what he’s doing recently:

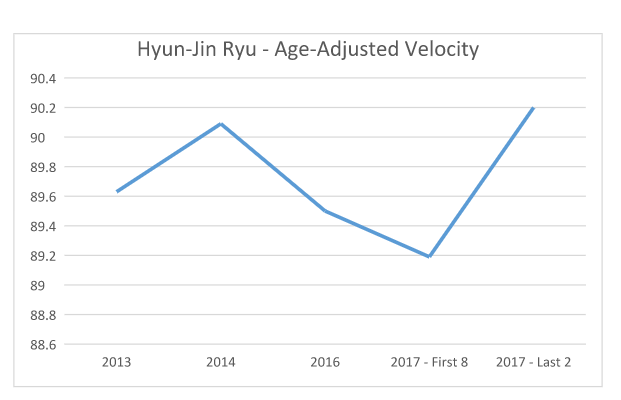

It’s been nearly three years, but Ryu finally is nearly back to the velocity he showed during his dominant first two seasons in America—which is particularly impressive given his age. And when you mathematically account for the expected age-related velocity decline, that 90.2 mph figure is effectively higher than the velocity he showed in either 2013 or 2014. When you adjust for age, this is how his velocity charts:

Sustaining the velocity of his past two starts would mark an MLB-career-high for Ryu. Had he been working with that effective velocity in 2013 or 2014, he’d have been even better!

(This is a good time to mention that THE BAT takes into account a pitcher’s velocity history, including his most recent few starts. A guy like Ryu who is throwing with increased velocity of late will be valued higher by THE BAT than a pitcher with the same stats but without increased recent velocity. To wit, Ryu currently projects for a context-neutral 8.1 K/9 by THE BAT.)

Any time a Dodgers pitcher shows flashes of talent, he immediately becomes interesting because of how fantastic the context is for their pitchers: they get to pitch in the National League, they get to pitch in a pitchers’ park in Dodgers Stadium, they get to throw to the two best pitch-framers in baseball in Yasmani Grandal and Austin Barnes, and they get to be supported by a great offense and an elite bullpen. In the right matchup, that can make even an average pitcher look great.

Ryu hasn’t been anything special yet this year. Even in his most recent two starts with the velocity spike, he’s only posted a 5.5 K/9 and 4.24 xFIP. They’ve been against good offenses in the Cardinals and Nationals, though, and results can have variance over a small sample. Velocity has much less, though, and while I’d like to see it for a couple more starts, a spike like this hints at good things to come.

The biggest limit on Ryu’s DFS value is his low pitch count. He’s averaged just 88 pitches this year, several times even getting the hook in the mid-70s. The Dodgers are notoriously quick with the hook and careful with their pitchers, and so I wouldn’t expect this to rise much. Still, they had extra reason to be careful with Ryu early in the year, and he did crack 100 twice over his last four starts. It’s unlikely he’ll be GPP-relevant anytime soon with a limited ceiling, but in the right match-ups he could absolutely be worth a look as a cash game SP2 if he remains priced in the $7,000 range.

Rising… And Bound To Be Way Overhyped

Seth Lugo, SP, New York Mets

Seth Lugo made his 2017 MLB debut this past weekend and dominated the Braves in SunTrust Park, which means just one thing: we’re going to start hearing a lot about what a sneaky-good play he is because of his elite curveball spin rate. After all, Lugo’s curveball spins 3295 revolutions per minute—34% more than league average, which ranks as the best in baseball among those who threw at least 100 curves in 2016 (and second place was just 22% better than average). Put like that, he sounds really good. The only problem? Spin rate doesn’t actually matter much for curveballs.

There is so much new data out now there with the advent of Statcast, and people love to rush to make use of that data, failing to stop along the way to test the underlying assumptions. One of those assumptions is that spin rate is a good thing. It seems obvious enough that it would be, so most assume we don’t even need to test it. But that assumption is wrong, at least for curveballs. For fastballs, spin rate is extremely important. For curveballs, it’s not nearly as much and there are a few reasons why.

1) Not All Spin is Useful Spin

There are actually two types of spin: transverse spin and gyro spin (or, “useful spin” and “useless spin”). Because a ball is spherical and moves through the air in three dimensions, it spins in more than one direction. Transverse spin is spin that is perpendicular to the direction of movement, and gyro spin is spin parallel to the direction of movement. This is just the science-y way of saying that transverse spin affects how much the ball moves and that gyro spin doesn’t affect movement.

While gyro (aka “useless”) spin can be effective for some pitches (it seems to be particularly effective for change-ups, likely adding deception to a pitch that is predicated on deception), it doesn’t seem to be effective for curveballs. It’s essentially wasted spin.

When you add the two together, you get the total “Spin” number that Statcast gives. For curveballs, only about 55% of spin (on average) is “useful” spin, and that number can change drastically from pitcher-to-pitcher, so using the total, unadjusted Spin figure from Statcast can be misleading.

Even if we were to isolate the “useful” spin for a pitcher’s curveball and use that instead (Lugo ranked third in baseball in useful spin last year among those who threw 100 curves—still elite), there’s still one more bad assumption we’d be making…

2) Movement isn’t necessarily a good thing

If you’ll recall from my article on Alex Wood, I talked about how the most effective curves are the ones that are fast, kept low in the zone, and hide well inside a pitcher’s fastball. This comes at the expense of movement. To get big movement on a curveball, that generally necessitates a bigger hump on the curveball like the kind in the John Lamb side-by-side graph. In 2016, Wood got just 1.6 inches of vertical movement and Lamb got 6.3, but Wood’s curveball was one of the best in baseball and Lamb’s was one of the worst. Wood’s spin rate was 1915 rpm and Lamb’s was 2161 rpm. But Wood’s curveball doesn’t want movement—at least not total movement. It wants very little movement at the start of the trajectory so it can hide for as much of the trajectory as possible and then get just enough movement at the end of the path so hitters swing over it when they think it’s a fastball.

Of course, pitchers can be effective with big movement—just in different ways. Look at Rich Hill. His curve gets big movement and has a big hump, but it’s effective anyway, particularly because he can drop it so well into the top of the zone for a called strike or generate groundballs when hitters do swing and make contact. But it’s a much finer line to walk.

3) Curveballs simply have more important elements than spin

It’s difficult to talk about curveballs and not seem to contradict yourself because there are so many variables that impact how good any particular curveball is. Some variables may be good for one type of outcome but bad for another. Some variables can only be good at the expense of making another variable bad. I’ve mentioned before that this winter I ran a battery of tests to create a system to quantify pitcher “stuff,” examining hundreds of variables to identify what is most important for each pitch type. In broad strokes, velocity and tunneling are ideal for curves while movement and spin tend to be less effective—in large part because to be good at one you have to sacrifice the other.

While spin is among the top 5 most important variables for fastballs, it’s ranked something like 50th for curveball swinging strikes and 20th for called strikes (both adjusted for count) with a very weak 0.06 and 0.10 Pearson correlation, respectively. Jeff Zimmerman at FanGraphs came to a similar conclusion — that velocity is great for curveball whiffs, but spin is only okay. What spin is good for is groundballs. If you break spin down into the two components, “useful” spin correlates with groundballs at 0.25. Total spin (the kind Statcast presents), however, is just 0.09. You’d be better off ignoring the Statcast data entirely and just using the PITCHf/x movement data (which correlates strongly with “useful” spin) that’s been around since 2007.

It sounds counter-intuitive (you’d think a good curveball is one that curves!), but movement can actually be a bad thing for curveballs (especially in a DFS sense) because of the related sacrifices.

How This All Relates to Seth Lugo

So circling back to Lugo, the bottom-line is this: he’s just not a very good pitcher. His curveball is actually a good pitch, but not necessarily because of the spin rate. Spin rate alone does not make a pitch—particularly a curveball — a good pitch. What it does make it is a pitch with more movement, but movement for curves generally leads to more groundballs and fewer whiffs—not especially desirable in DFS where we prioritize Ks. Lugo’s curve does enough other things to project for an above-average K%, but even so, he only throws his hook 15% of the time anyway. He throws his slider (a solid but worse pitch) more often at 18%, a bad change-up at 8%, and two terrible fastballs nearly a combined 60% of the time. If one of those fastballs ever gets better he could be an intriguing breakout candidate, but until that happens he’s a guy who’s going to receive more hype than he deserves based on the hot new toy that most people don’t actually really understand. After all, he posted just a 4.71 xFIP with the Mets last year and wholly mediocre numbers throughout his minor league career.

He might be GPP-relevant in the right matchups—he does call Citi Field home and throws to a pair of good pitch-framing catchers—but that’s about it. If people try to tell you that Lugo is this sneaky-great pitcher because of his curveball’s spin rate, you can safely ignore them.