2018 MLB Risers and Fallers: Volume 3

Welcome back to another season of Risers & Fallers! Last year in this space, I turned you onto first-half Alex Wood because of his increased velocity and incredible curveball pitch tunneling. I told you Justin Verlander would be fine. I told you Seth Lugo’s insane curveball spin rate didn’t make him a good pitcher and that Aaron Nola’s low swinging strike percentage didn’t matter.

This is where I dive deep into the numbers and the narratives and see what’s real and what isn’t using advanced metrics, my DFS projection system (THE BAT, available in the RotoGrinders Marketplace), and insights from my scouting background. I’ll examine guys whose stock is going up, guys whose stock is going down, guys who are perpetually underpriced or overpriced, guys who are worth paying a premium for, or guys who are just interesting and warrant some analysis on.

Falling… Edge in DFS Contests (but it still exists if you look)

It’s funny, every year around this time I find myself thinking, “Damn, DFS players just keep getting smarter and smarter. A couple years ago, Player X would have only been 10% owned instead of 50%. The benefit from playing this guy would have been so much greater.” People are getting smarter, and the edge is getting smaller, but that doesn’t mean edge doesn’t still exist. People still focus way too much on single year stats. People still ignore or misjudge the concept of regression. People focus on pitcher skills but ignore how deep they tend to go into games. People ignore pinch hit risk. And on and on, there are still plenty of things that create edge. But a less obvious one may as well have smacked us in the face last night.

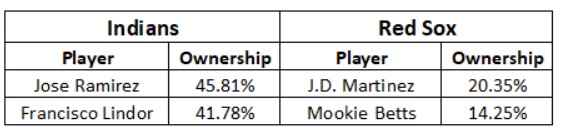

The top two offenses on the board were the Boston Red Sox (5.25 Vegas implied team total) and the Cleveland Indians (5.43). There was just an 0.18 difference in implied runs, and no other team was over 5.00 runs. Both teams had their two best players costing over $5,000 on DraftKings. So ownership was split pretty evenly between them, right? You’d think so, but nope. The Indians were extremely chalky, while the Red Sox merely got a fraction of the same ownership:

Yes, the Red Sox were facing Sean Manaea, which may have scared some people off. And yes, Lindor and Ramirez play shallower positions than J.D. and Mookie. But an ownership discrepancy this huge is just clearly wrong. This looks like free value for anyone running the actual math behind the plays.

What it comes down to this principle: when two teams project identically overall but one team is well-balanced and the other is more of a stars-and-scrubs lineup, the best players on the stars-and-scrubs team will be better plays than the best players on the well-balanced team. I know that’s slightly convoluted, so read it one more time and then I’ll explain further.

What I mean is that DFS players know how to look at matchups and at team totals, but far fewer of them think about how a team is projected to reach a team total. Teams are nothing more than a collection of players, and each player is expected to contribute a certain amount towards the total. Better players contribute more than worse players (obviously), and so if you’re playing someone because their team has a high total, it matters (a lot!) who the other players in the lineup are. Take a look at the true-talent of each player in the Red Sox and Indians lineup, according to THE BAT season-long projections (which you can now find at FanGraphs).

In addition to listing the projected wOBA of each player (which is the best estimate of real-world run-scoring value—i.e. the number that most affects a team total), I also give each team’s standard deviation, which is a measure of how closely grouped the players are. The standard deviation of the Red Sox lineup is much bigger than the Indians. That’s because they have two players who project for close to a .400 wOBA and one who projects under .300. It’s a “stars and scrubs” type lineup. The Indians, on the other hand, don’t have a single player either above .380 or under .300. It’s a much more balanced lineup.

As a result, when the Red Sox and Indians project for the same total, Mookie and J.D. are implicitly projected to be better at the plate than Lindor and Ramirez. Mookie and J.D. are better players with a worse surrounding lineup. Put that way, it’s painfully obvious they should contribute more. Mathematically, there’s just no other way (all else held constant).

Some may say, “Well Ramirez has had a .400+ wOBA since the start of 2017, he’s just as good as Mookie or J.D.!”, but they’d need to remember that there is a big difference between a player’s performance over any period of time (especially one with a conveniently chosen starting point) and his projected talent level going forward. THE BAT actually likes Ramirez more than the other systems. It gives him a .376 wOBA while Steamer and ZiPS are at .362 and .368, respectively. You can argue that Ramirez is on the same level as Mookie or J.D. based on this arbitrary cut-off, and if you truly believe that’s the case then that would change things. But the best public projection tools would all disagree with you.

Now obviously DFS roster construction requires you to consider more than just projected wOBA. How a player’s skills mesh with the site’s scoring system matters. Stolen bases matter. Pricing matters. Opportunity cost at each position matters. And on and on. But this is a great real-world example of how one crucial part of this process can go completely ignored. Ramirez and Lindor were good plays last night, but there’s a very strong case to be made they weren’t as good Mookie and J.D. were. And yet we saw soaring ownership on them, which makes me realize that while certain value routes have been closed, there are others that still exist.

It’s also worth noting that this type of thing is even more important when comparing American League to National League teams. Because NL teams have a pitcher in the lineup, who will contribute very little to the team total, the contribution of each of the remaining 8 hitters matters that much more.

All told, it’s important to remember: A “star” on one team is not equal to a “star” on another team, even if both teams have the same total. Additionally, one “star” is not always even of the same quality as another “star”. It’s easy to lump them together and say, “Yeah, well both are great players, I’ll just take whichever matchup I like better,” but if one is actually better than the other, you can get away with a lesser matchup.