NFL Best Ball Strategy: Buying Volatility

![]()

This article is going to focus on wide receivers, but it’s really about roster construction. The goal of this whole series on Best Ball strategy is to get you thinking about your picks within the context of your specific team, and maximizing the value of each player on your roster. Not all fantasy points are the same – we want to collect the ones that are actually going to hit our starting lineup. That’s the bottom line.

I mentioned in the first article of this series that we want to target “boom/bust” players in Best Ball drafts. I want to revisit that idea in more detail now. One thing I want to make clear is that targeting players we expect to exhibit high weekly volatility has everything to do with the Best Ball format, and nothing to do with how top-heavy the prize structure may be (this seems to be a common misconception). We are not taking on more risk with a “first or last” mindset. In fact, we can use volatile players to reduce the risk profile of our roster while increasing its upside. It’s all about how the players fit together.

Targeting volatile players in Best Ball isn’t new – most drafters have caught onto the idea, but I’m not sure everyone appreciates how important volatility really is. By far, the biggest driver of ADP within a position is expected production, even in Best Ball, and it should be. But, the way in which players get those points does not move the needle as much as I think it should. We are going to be buyers of underpriced volatility.

Editor’s Note: Use promo code “GRINDERS” when you sign up for Draft and get a 100% deposit bonus up to $600 and THREE months of RotoGrinders Draft Premium content!

Volatility Matters

The table below shows two groups of nine wide receivers, along with their stats from weeks 1-16 of 2016 (our fantasy teams don’t get credit for week 17 points). Team A exclusively drafted volatile wide receivers, while Team B’s group comprises only consistent week-to-week producers.

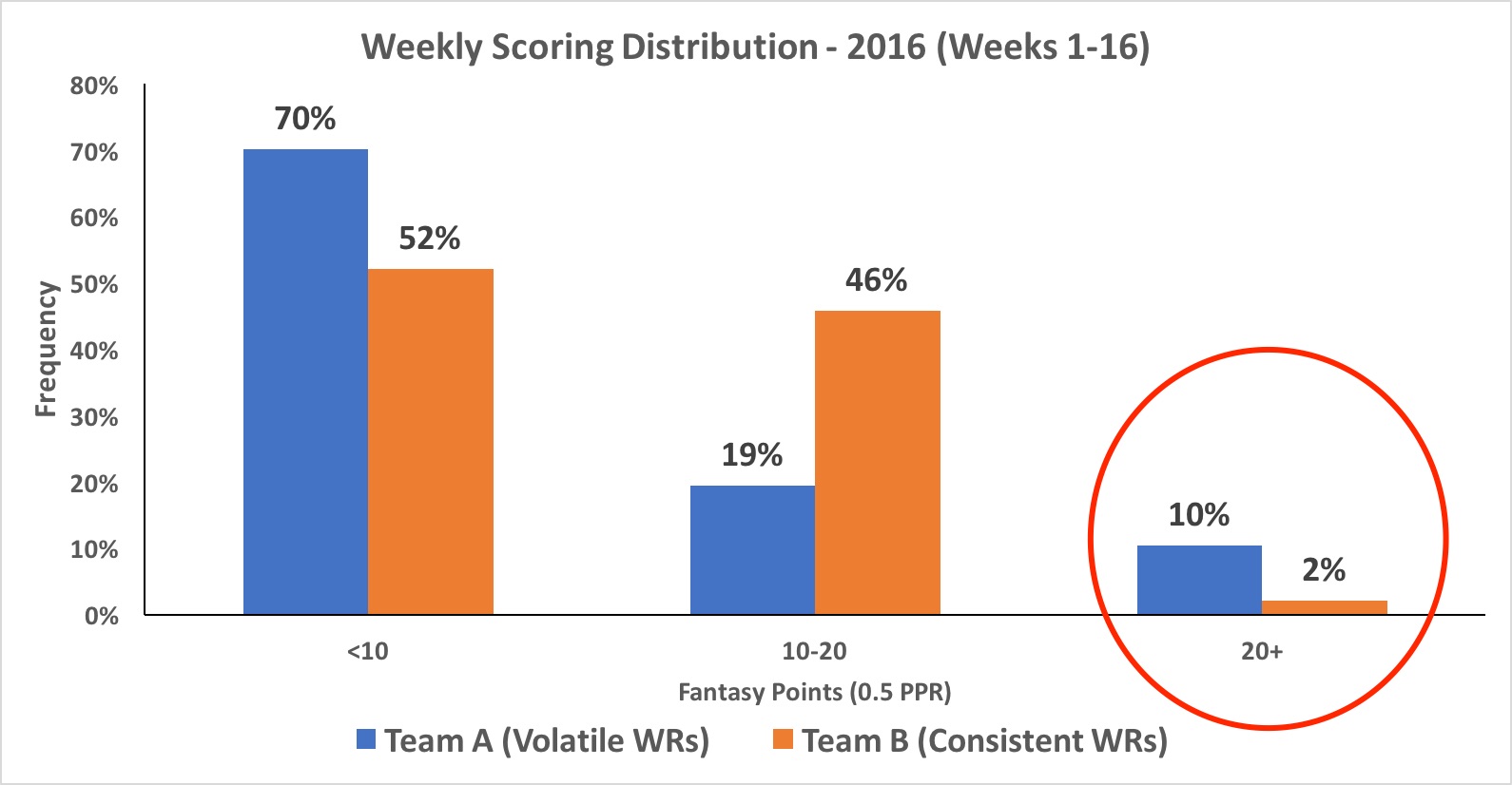

Based on these tables, it looks like Team B drafted a much better group. Combined, they scored 220.5 more points than Team A’s wide receivers, through both a higher per-game average and better injury luck… BUT, how many of those points did each team actually count toward their final score? Again, we have to focus on the bottom line.

In Draft Best Ball leagues (and leagues on many other sites), we have to fill three starting wide receiver positions each week, and we can use as many as four wide receivers, if one is needed for the “Flex” position. So, if we take just the top three scores from each team’s wide receivers each week, we find that Team A actually outscored Team B at the starting WR positions by about 47 points (724.5 for Team A vs. 677.8 for Team B). The team that had 220 fewer points to work with scored almost 50 more at the position! The implications here are huge. But before we go there, how does this happen?

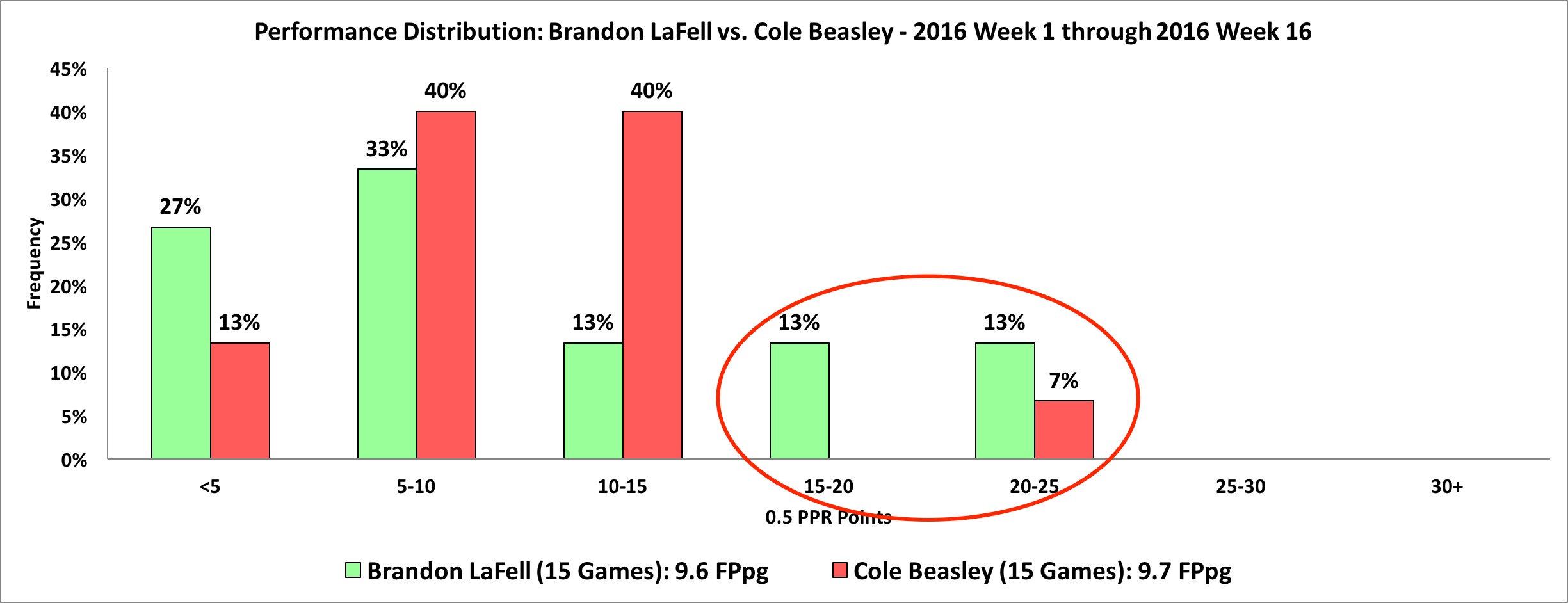

If you have been following this series, or checking in on the weekly Best Ball Value Watch, you’ll recognize this type of chart. It compares two players, in this case Brandon LaFell and Cole Beasley, by breaking down their weekly scores by how often they fall into different point ranges. I like this chart because you can very quickly see who provided more weekly upside. Here, we can see that LaFell provided more big games last year, breaking 15 points four times in 15 games (~27 percent), while Beasley had only one game over 15. Conversely, LaFell had more duds, with just as many games going for under five points – Beasley had a better floor.

Accordingly, LaFell is on “Team Volatility” while Beasley is a member of “Team Consistency.” What does this chart look like for each team as a whole? The chart above does not include bye weeks or missed games, but our rosters don’t get a free pass for those zeroes, so I have included all 144 games in the combined chart (nine players x 16 weeks). This chart tells the story.

Team A was able to outscore Team B, despite 70% of its weekly scores coming in under ten points, because it was able to generate enough big games to fill the starting positions each week. While nine wide receivers will generate 144 weekly scores over the course of a 16-week season, we only need to use 48 of them, and Team A mustered 48 good ones, including 15 games of over 20 points, vs. only 3 such games for Team B.

Note: For completeness’ sake, Team A also outscored Team B assuming WRs were used in the Flex each week (i.e. we took the top four scores each week instead of three), but the margin was smaller, at 10 points.

Implementation – Quantity over “Quality”

Now that we have established that volatility can be a very good thing, how do we use it to our greatest advantage? The point of the preceding exercise was not to tell you to ignore good, consistent wide receivers. The point was to highlight the power of efficient roster construction. I mentioned in the intro that we could use this information to reduce risk without sacrificing upside. What makes that possible is where we can find the volatile receivers in the draft.

Based on the win rate data referenced in my ADP Sweet Spots article, it is extremely difficult to find valuable running backs in the late rounds of these drafts. Win rates at the position are low, fantasy scoring is low (especially in half-PPR formats like Draft), and a large proportion of running back picks made in a round ending in “teen” require something to happen (e.g. an injury to a teammate) before they are likely to contribute – relying on those picks to carry your team is extremely risky. The late rounds are littered with boom/bust wide receivers, however. Five of the nine wide receivers on Team A above had an ADP in the 17th round or later in MyFantasyLeague.com Best Ball leagues last year, and only two of them came from the first six rounds. Knowing these high-volatility wide receivers are waiting for us in the double-digit rounds allows ups to load up on more reliable running backs early in the draft.

If you are going to take this approach, though, you must be prepared to hit the high end of our 6-9 WR range by the end of the draft (i.e. eight or nine). Knowing these players have low floors, we need more chances each week to hit the big scores and fill all three WR slots with solid totals. Conversely, if you opt for a premium wide receiver in one of the early rounds – one who is likely to fill 12-15 starts on his own, the eighth and especially the ninth wide receiver, even if they are very volatile producers, lose significant value for your team, and the picks should be used to bolster other positions.

Volatility Arbitrage

Favoring volatility and quantity allows you to wait longer to draft your wide receivers. Here are a few examples of players I target (and avoid) when I decide to go this route.

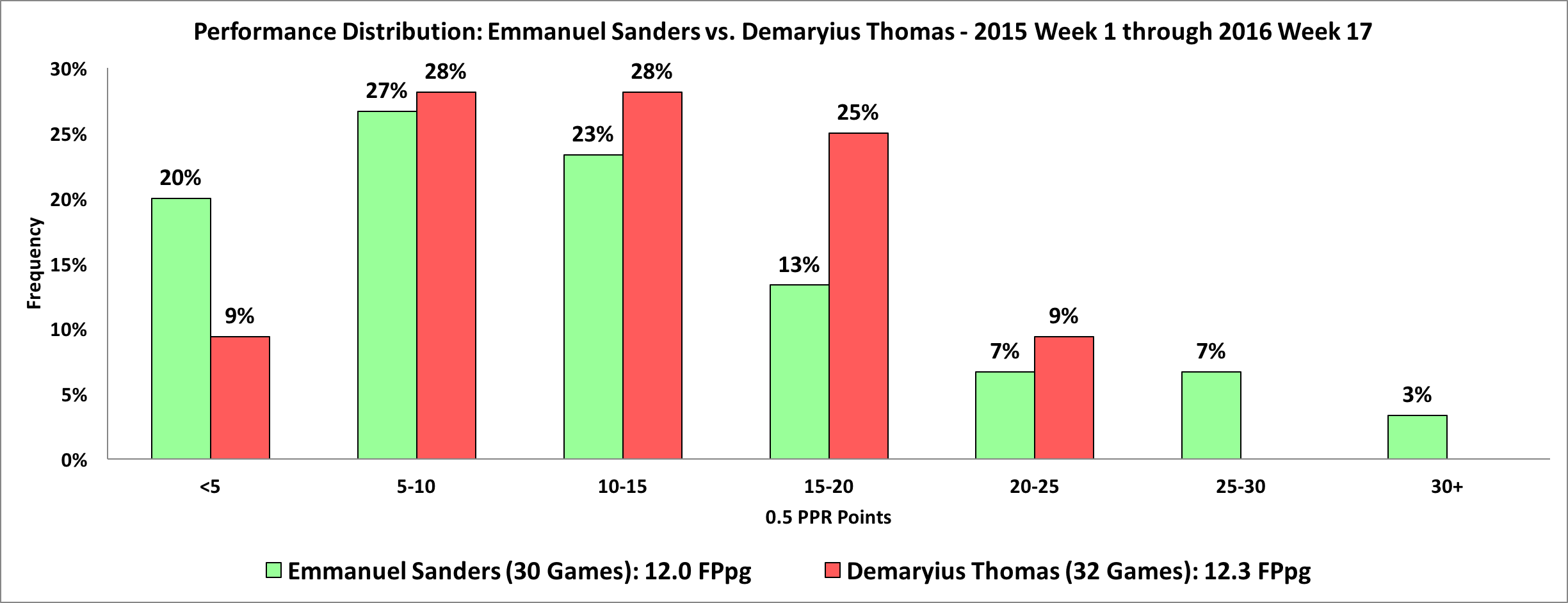

Emmanuel Sanders (ADP: 58 Overall) INSTEAD OF Demaryius Thomas (ADP: 33 Overall)

Over the past two seasons, teammates Demaryius Thomas and Emmanuel Sanders have generated similar year-end fantasy totals, but they have done it in very different ways. Thomas has been as steady as it gets, thriving between the 20s on high target volume. Sanders, meanwhile, has collected his points in bunches. Two rounds later than Thomas in ADP, Sanders is a great piece for a deeper, high-volatility WR corps.

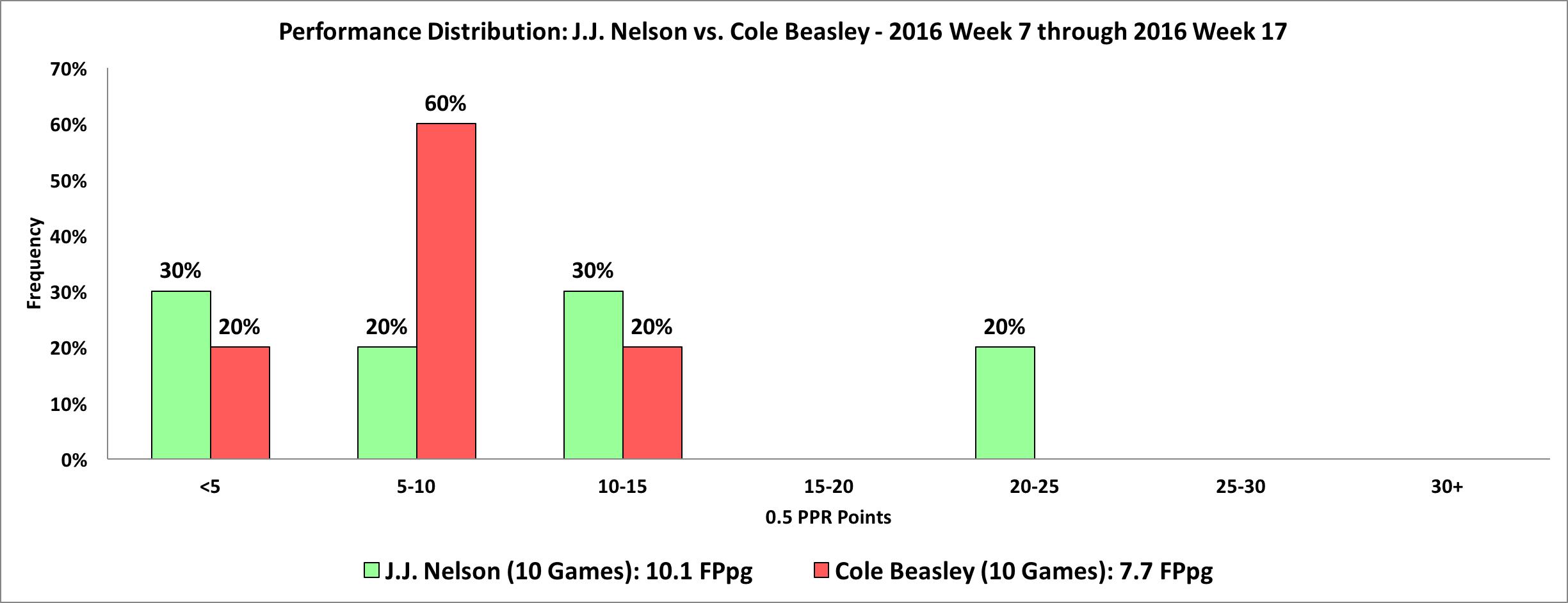

J.J. Nelson (ADP: 163 Overall) INSTEAD OF Cole Beasley (ADP: 153 Overall)

Beasley seems to be a somewhat trendy pick in the fantasy analyst community, but I can’t get behind him as a late round pick in Best Ball. Beasley has a decent weekly floor, but wide receiver floor just isn’t a priority here. J.J. Nelson, meanwhile, is cheaper and offers a deep game with much greater weekly upside. Starting in week seven of last year, the first week that Nelson received more than two targets, Nelson both outscored Beasley on a per game basis and produced more big games. The second half of the year is also likely a better representation of Beasley’s true usage, given that Dez Bryant was hobbled, or absent, the majority of the first half.

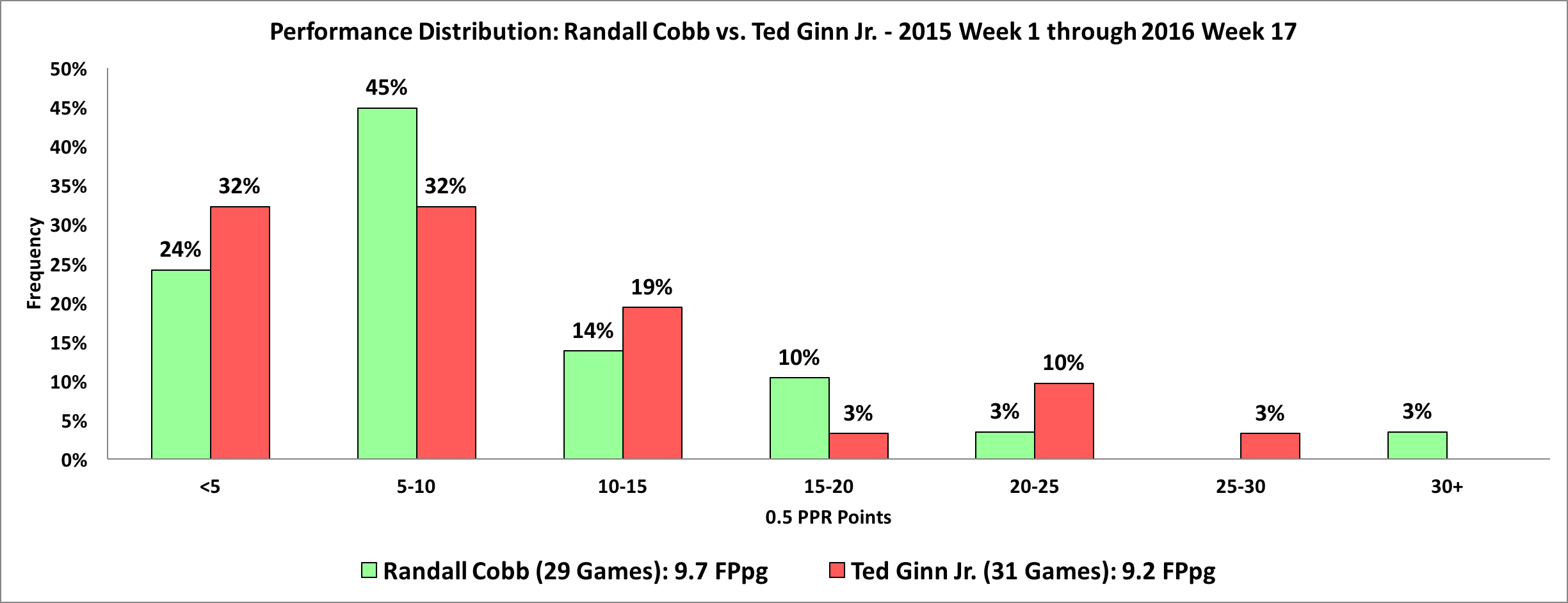

Ted Ginn (ADP: 111 Overall) INSTEAD OF Randall Cobb (ADP: 73 Overall)

The days of Randall Cobb, WR1, are a distant memory at this point. Over the past two seasons, Cobb, when healthy, has done a nice job as a chain mover for the Packers, but he has fallen behind Jordy Nelson and Davante Adams as go-to options when Aaron Rodgers is thinking big play, or end-zone. The addition of Martellus Bennett cuts even deeper into Cobb’s potential for big games. Ginn, meanwhile, has moved to a dome in New Orleans where his job will be to run under picturesque Drew Brees deep balls. The deep specialist with notoriously poor hands certainly won’t catch all of those bombs, but it will not take many connections for Ginn turn in a strong contribution to your Best Ball scores.

Conclusion

There are many ways to win at Best Ball, and the goal here was to convince you that a high quantity, high volatility approach to WR is among the better ones. I do not hate “high floor” wide receivers, and I do not hate expensive wide receivers – they have a place on many of my rosters, and I adjust my approach to the rest of the draft when value dictates that I pick them. That said, I have found myself favoring the RB early, volatile WR late, strategy more often than not this year, especially on Draft, where the 0.5 PPR scoring limits and already wanting late running back pool.

Ultimately, this approach is just another tool in our kit, a kit that we want to be as robust as possible. Until next week, good luck everyone!